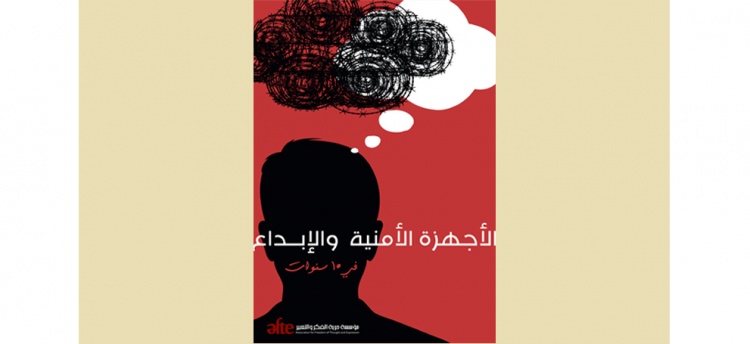

Association for Free Thought and Expression Publishes Paper: Security Forces and Creativity in Past Ten Years

Mar 2016Written by: Hossam Fazulla

Edited by: Mustafa Shawqi

The last ten years—and particularly those preceding the Egyptian Revolution of 2011—have been characterised as something of a dry spell in Egyptian society. In fact, all outlets in the public domain had been so closed-off that that society could more properly be described as “barren”. This coincided with widespread repression, plans to bequeath state powers, and the then-ruling National Democratic Party's monopoly over all aspects of the state.

The success of the revolution's initial stages—ushered by former President Mubarak's resignation on February 11th, 2011—saw a sudden burst of creativity from thousands of young Egyptians artists, an outburst preceded by decades of ignorance, intolerance, and a culture dictated by a single overriding mindset. These moments and subsequent ones like them offered the hope of freeing society from its various chains and allowing it toflourish; this included the liberation of culture, creativity, and artistic life.

However, these promises did not come to fruition. In spite of the diversity of ideologies and schools of thought in the country – and for numerous reasons not relevant to the topic at hand – regulations were adopted to maintain the core policy of the old regime.

The Association for Free Thought and Expression (AFTE) has observed that over the past nine years (2007-¬2015), security forces have continued to shape cultural activity in Egypt, supported by policies consistent with those used under the old state. This has meant that security services have infringed on creative and cultural rights within Egyptian society,violating the Constitution, various laws, and international conventions demanding the protection of the right to freedom of artistic expression. This places us in a situation similar to that pre-2011.

AFTE researchers have observed security forces and highlighted methods with which they violate these institutions, grouping them into six different but recurrent actions. These methods existed before and the revolution and remain in place today. They are as follows:

One: Involvement in the content of art, whether through banning or editing (acting as censors).

Despite the Censorship Board being the only body legally entrusted to oversee audio and audiovisual work in Egypt (giving the green light to filming, screening, broadcasting, selling, trading, or transferring artwork, all in accordance to Article 2 of Law No. 430 of 1955 of the Regulations issued by the Prime Minister in decision No. 126 in the year 1993), it simply passes any work to which it suspects security forces might object, to the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of the Interior. This is done unofficially and without a legal prerequisite. The Ministries then evaluate the work and decide whether to leave it unedited, change it, or ban it outright.

This type of violation occurred, for example, with Al-Musheer wal Ra'ees (The Field Marshal and President), directed by Khaled Youssef and written by Mamdouh al-Laithi. Here, shooting rights were suspended until the film received approval from both Egyptian and military intelligence. This prompted the director to file a lawsuit at the Administrative Judiciary Court for the illegal procedure undertaken by the Censorship Board. The court revoked the Censorship Board's decision, allowing the film to commence shooting on March 10th, 2010.

Two: Book Confiscation Through Customs or by Withdrawing Market Copies

Publications Law No. (20/1935), as amended by Law No. (199 for 1983), is mandated with censoring publications in Egypt. Within its domain are: monitoring and censoring books, preventing their publication and distribution, and administrative confiscation of books without recourse to judicial authorities. All of these duties are dependent on whether the book's content is illegal or somehow threatens national security.

But, of course, that is never the way things go; different security agencies confiscate books and other published materials either at customs or by withdrawing copies from bookshops and libraries. This happens for reasons determined by the authorities, without any role or legal status, mostly for political, religious, or moral reasons. Security forces' actions do not stop at (illegal) censorship of audio and audiovisual art, but extend to publications in all their forms. These entities require a secure grip on all aspects of creative life in Egypt.

A prominent example of this violation comes in the form of Musta'edeen lilIjabeh (We Are Ready to Answer) by Sameer Markas, in 2009. The book contrasts Christianity against Islam, prompting Dr Mohammed Amara at the Centre for Islamic Research at Al-Azhar University to draft a book giving a scientific analysis of the issue, in response. The exchange was considered a prominent example of what freedom of speech should be like in this day and age: answering ideas with ideas. However, security forces had ideas of their own, banning Al-Azhar's book after doing the same for We Are Ready to Answer.

Three: Breaking into publishing houses and publishers' residences

On February 2nd, 2010,a day before the Libyan-Egyptian summit in Sirte between former Presidents Mubarak and Gaddafi, the Wa'ad Publishing House was broken into, its owner Al-Jameeli Ahmed Shahateh arrested, and all copies of Idris Ali's novel Al-Za'eem Yahlek Sha'areh (The Boss Cuts His Hair) seized, on the accusation that the novel offends the Republic of Libya and its president, and due to the novel's use of swearwords. The publisher was held for two days, during which time it became apparent that the novel, despite containing “immoral” swearwords, neither attacked Libya nor its president. The book was banned from the Egyptian market until 2011, after the fall of both Mubarak and Gaddafi.

In April 2010, security forces broke into the residence of Ahmed Mehni, manager of the Dor Publishing House, a week after publishing Kamal Gibril's Al-Baradiee wa Hilm al-Thawra al-Khadra'a (Al-Baradiee and the Dream of the Green Revolution). Mehni's books were confiscated, including sixteen copies of Gibril's books. He was later released.

Four: Preventing Art Events

Before the revolution, it was the right of the Ministry of the Interior – under the pretext of Emergency Law –to prevent any activity, even celebratory, that had not been given permission. In any case, no public spaces were allocated for street art or for any large-scale cultural or literary activities.

Al-Fan Midan was among the most prominent art events banned by security forces in recent years. It was a monthly festival starting in February 2011 which celebrated the revolution and took place in Abdeen Square in Cairo. The event spread to Alexandria, Suez, and other provinces including Damietta, Port Said, Al Sharqia, Luxor, Aswan, Isamailia, New Valley Governorate, and Mansoura.

The festival included various kinds of art, rekindling interest in the arts and theatre in Egypt, and unlocked the talent of thousands of young artists in Egypt. It was supported through donation and self-funding. The Ministry of Culture gave it a grant from the then-ruling army-led parliament, plus financial support in October 2011, which latterly ceased.

In November 2013, after declaring an anti-protesting law which prevents protests without governmental issue, pressure directed at any sort of gathering increase – even those intended as celebrations and art. Al-Fan Midan ceased in 2014 after its organisers surrendered to all the obstacles deployed by the government, including arrest and imprisonment.

Five: Arbitrary Refusal to Granting Filming Permits

One of the most prominent ways with which security forces have intervened in art is seen in the Ministry of the Interior's exclusive authority to prevent filming in public spaces. Public photography and filming (even for personal use) without receiving authorisation is illegal.

In January 2011, documentary filmmaker Hossam Salman, and Jeremy Hodge, an American translator, were arrested at their residence by Homeland Security for filming in the street. They were accused of disseminating false information to imbalance national security, an accusation irrelevant to their activities. The pair was not allowed access to lawyers for their case.

Six: Arresting Publishers and Artists

AFTE considers this type of violation to be the most serious, excluding the beating the photographer Hossam Salman while he was detained in custody.

The rising creative efforts following the Egyptian Revolution largely manifested as street art, a form which inherently demands an audience. This is a cause of concern for repressive regimes. In addition to their opposition to any mass gatherings, they oppose art events which enrich awareness, openness, and discourse; it is these progressive ideas which regimes fear will spread.

In September 2013, Gen. Adel Labeeb, Minister for Local Development, announced that severe punishments would be issued to anyone caught writing on walls. The Minister issued the warning on the pretext it was bad for the environment. Forms of punishment ranged from financial penalty to imprisonment. This was declared months before anti-protest laws were put into action, greatly reducing the presence of street art, graffiti, music festivals, and other performance art. The situation has worsened to the point that even the government has had to reduce its own illegal violations as activists have been continually repressed.